In brief

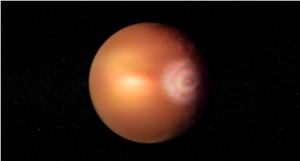

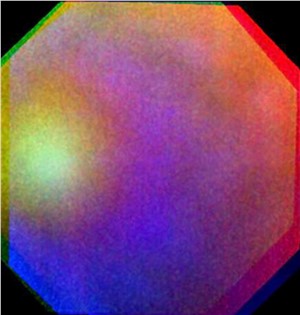

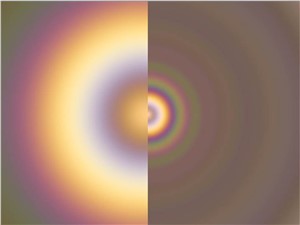

For the first time, potential signs of the rainbow-like ‘glory effect’ have been detected on a planet outside our Solar System. Glory are colourful concentric rings of light that occur only under peculiar conditions.

Data from ESA’s sensitive Characterising ExOplanet Satellite, Cheops, along with several other ESA and NASA missions, suggest this delicate phenomenon is beaming straight at Earth from the hellish atmosphere of ultra-hot gas giant WASP-76b, 637 light-years away.

Seen often on Earth, the effect has only been found once on another planet, Venus. If confirmed, this first extrasolar glory will reveal more about the nature of this puzzling exoplanet, with exciting lessons for how to better understand strange, distant worlds.

by Laser Type (Semiconductor Diode, Fiber, Solid-state), Data Rate (< 2.5, 2.5-10, > 10 GBPs), Platform, Application, Component and Region

Download free sample pagesIn-depth

Data from Cheops and its friends suggest that between the unbearable heat and light of exoplanet WASP-76b’s sunlit face, and the endless night of its dark side, may be the first extrasolar ‘glory’. The effect, similar to a rainbow, occurs when light is reflected off clouds made up of a perfectly uniform but so far unknown substance.

“There's a reason no glory has been seen before outside our Solar System – it requires very peculiar conditions,” explains Olivier Demangeon, astronomer at the Instituto de Astrofísica e Ciências do Espaço (Institute of Astrophysics and Space Sciences) in Portugal and lead author of the study.

“First, you need atmospheric particles that are close-to-perfectly spherical, completely uniform and stable enough to be observed over a long time. The planet's nearby star needs to shine directly at it, with the observer – here Cheops – at just the right orientation.”

If confirmed, this first exoplanetary glory would provide a beautiful tool to understand more about the planet and star that formed it.

“What’s important to keep in mind is the incredible scale of what we’re witnessing,” explains Matthew Standing, an ESA Research Fellow studying exoplanets.

“WASP-76b is several hundred light-years away – an intensely hot gas giant planet where it likely rains molten iron. Despite the chaos, it looks like we’ve detected the potential signs of a glory. It’s an incredibly faint signal.”

This result demonstrates the power of ESA's Cheops mission to detect subtle, never-seen-before phenomena on faraway worlds.

A hellish planet with lopsided limbs

WASP-76b is an ultra-hot Jupiter-like planet. While it is 10% less massive than our striped cousin, it is almost double its size. Tightly orbiting its host star twelve times closer than scorched Mercury orbits our Sun, the exoplanet is ‘puffed up’ by intense radiation.

Since its discovery in 2013, WASP-76b has come under intense scrutiny and a bizarrely hellish picture has emerged. One side of the planet always faces the Sun, reaching temperatures of 2400 degrees Celsius. Here, elements that would form rocks on Earth melt and evaporate, only to condense on the slightly cooler night side, creating iron clouds that drip molten iron rain.

But scientists have been puzzled by an apparent asymmetry, or wonkiness, in WASP-76b’s ‘limbs’ – its outermost regions seen as it passes in front of its host star.

Data from different ESA and NASA missions including TESS, Hubble and Spitzer, were also analysed in this revealing study, but it was when ESA’s Cheops and NASA’s TESS worked together that hints of the glory phenomenon began to appear.

Cheops intensively monitored WASP-76b as it passed in front of and around its Sun-like star. After 23 observations over three years, the data showed a surprising increase in the amount of light coming from the planet’s eastern ‘terminator’ – the boundary where night meets day. This allowed scientists to disentangle and constrain the origin of the signal.

“This is the first time that such a sharp change has been detected in the brightness of an exoplanet, its ‘phase curve’,” explains Olivier.

“This discovery leads us to hypothesise that this unexpected glow could be caused by a strong, localised and anisotropic (directionally dependent) reflection – the glory effect.”

Basking in WASP-76b’s reflected glory

While the glory effect creates rainbow-like patterns, the two aren’t the same. Rainbows form as sunlight passes through one medium with a certain density to a medium with a different density – for example from air to water – which causes its path to bend (refract). Different wavelengths are bent by different amounts, causing white light to split into its various colours and creating the familiar round arc of a rainbow.

Glory, however, are formed when light passes between a narrow opening, for example between water droplets in clouds or fog. Again, light’s path is bent (in this case diffracted), most often creating concentric rings of colour, with interference between light waves creating patterns of bright and dark rings.

What the first far-flung glory would mean

Confirmation of the glory effect would mean the presence of clouds made up of perfectly spherical droplets, that have lasted at least three years or are being constantly replenished. For such clouds to persist, the temperature of the atmosphere would also need to be stable over time – a fascinating and detailed insight into what could be going on at WASP-76b.

Importantly, being able to detect such minute wonders so far away will teach scientists and engineers how to detect other hard-to-see but critical phenomena. For example, sunlight reflecting off liquid lakes and oceans – a requirement for habitability.

Glorious proof on the horizon

“Further proof is needed to say conclusively that this intriguing ‘extra light’ is a rare glory,” explains Theresa Lüftinger, Project Scientist for ESA’s upcoming Ariel mission.

“Follow-up observations from the NIRSPEC instrument onboard the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope could do just the job. Or ESA’s upcoming Ariel mission could prove its presence. We could even find more gloriously revealing colours shining from other exoplanets.”

Olivier concludes: “I was involved in the first detection of asymmetrical light coming from this weird planet – and ever since I have been so curious about the cause. It has taken some time to get here, with moments where I asked myself – ‘Why are you insisting on this? It might be better to do something else with your time.’ But when this feature appeared out of the data, it was such a special feeling – a particular satisfaction that doesn’t happen every day.”