This was the third successful deep drilling test on Earth for the European wheeled laboratory, an operation crucial to answer the question of whether there was, or is, life on the Red Planet.

A year has passed since the launch of the rover mission was put on hold and then cancelled, but the work has not stopped for the ExoMars teams in Europe. Today ESA, together with international and industrial partners, is reshaping the ExoMars Rosalind Franklin mission with new European elements and a target date of 2028 for the trip to Mars.

Amalia, the rover test model, has not been idle or far from its twin. The Rosalind Franklin rover, the one that will fly to Mars, patiently awaits in the ultra-clean room of Thales Alenia Space in Turin, Italy. Fully representative of what Rosalind will do on the Red Planet, engineers used the Amalia rover to scout a Mars terrain simulator at the ALTEC premises in the search for a drilling spot.

By Orbit Type (LEO, MEO, GEO, Others), by Architecture (Transparent Payload, Regenerative Payload), by Service Type (Fixed Satellite Service, Mobile Satellite Service, Broadband Satellite Service, Others), by End-User (Telecommunication, Government, Defense, Aviation, Others) and Region, with Forecasts from 2025 to 2034

Download free sample pagesDeep drilling

Amalia took its time to perforate a well filled with soil – soft silica on the surface, followed by layers of sand and fine volcanic soil, all of them resembling what Rosalind the rover could encounter under the martian surface.

On day three of the test excavation, the drill stretched almost to its maximum and reached its target – a gypsum mineral from the Turin region, commonly found in sedimentary deposits linked to water.

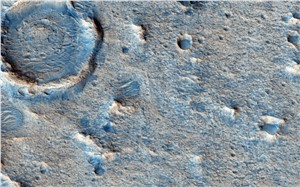

The finding was relevant to Mars geology because the targeted landing site for the rover, Oxia Planum, is an area where sediments might preserve traces of an ancient water-rich Mars environment. Oxia Planum will be the geologically oldest landing site visited on Mars when Rosalind Franklin lands there in 2030.

Scientists want to go very deep to access to well-preserved organic material from four billion years ago, when conditions on the surface of Mars were more like those on infant Earth and the area could have hosted micro-organisms.

The record for the deepest any drill has dug and sampled on the Red Planet to date is 7.1 cm, and it currently belongs to NASA’s Perseverance rover.

Precious sampling

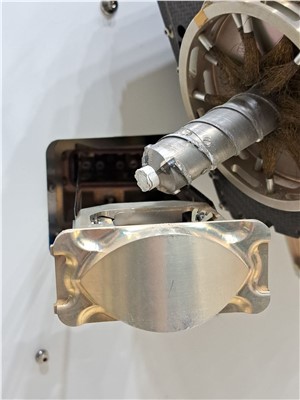

The test in Turin with Amalia was considered a success when, on day four, the drill acquired a sample in the shape of a pellet of about 1 cm in diameter and delivered it to the laboratory that is inside the rover’s belly.

Once the drill was completely retracted, the pellet was dropped into a drawer that withdrew and transferred the sample into a crushing station. The resulting powder will be distributed to ovens and containers for scientific analysis.

The whole operation was assisted by the eyes of the rover. The Panoramic Camera suite, known as PanCam, used its high-resolution camera to closely examine rock texture and grain size in colour.

On Mars, this powerful camera will help investigate very fine details in outcrops, rocks and soils from a distance, find the most promising spots to drill, and then take high resolution images of the samples sitting in the holder of the core sample transfer mechanism, before they are sent to the rover’s laboratory.

At the same time, the Close-Up Imager, CLUPI, mounted on the outside of the drill itself, provided detailed views of the soil tailings pile churned out by the drilling action, as well as of the sample in the holder on its way to the lab.

The reliable acquisition of deep samples that are preserved from the harsh radiation environment at the surface is key for ExoMars’ main science objective: to investigate the chemical composition of the soil, and with it, possible signs of life.

The drill was developed by Italian company Leonardo, while Thales Alenia Space is the prime contractor for ExoMars.

Driver’s seat

The data coming in from the deep drilling simulation in chorus with the science instruments was the baseline for more tests. The science team at the control room received a mix of data from the test, simulated data from other Mars-like samples and a set of images of the sample and the drilling spot.

Scientists were confronted with the challenge of reacting quickly and coming up with a plan of activities for the next sol, or martian day, that would be sent to the rover on Mars.

“These simulations are valuable because they put us in the driver’s seat in an immersive environment – so that we can practice and refine how we will run Rosalind Franklin rover operations,” explains Elliot Sefton-Nash, a project scientist for the ExoMars Rosalind Franklin Mission.